On May 29, King & Wood Mallesons, the International Law Association (Victoria Chapter) and the Australian Red Cross organized an event on “The Responsibility to Protect: Where to from here?” featuring presentations from leading R2P experts Gareth Evans, Damien Kingsbury and Phoebe Wynn-Pope.

Even if it is often seen as synonymous with humanitarian intervention, R2P has its origins as a principle of international law in the Report of the International on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICSS) of 2001. As Damien Kingsbury noted, even if a moral principle informs the two concepts, humanitarian intervention and R2P have different scopes. In a nutshell, the R2P principle aims at the protection of the most vulnerable populations from the most heinous international crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing. To Professor Evans, the principle has the virtue to have introduced the language of protection in the dominant discourse of state sovereignty, usually characterized by its “conspicuous indifference” towards state misbehavior vis-à-vis its own people. He also offered a brilliant walkthrough on the life stages of R2P by distinguishing three phases: (i) birth and early childhood (2001-2005): from its inception in the 2001 Report to its endorsement by heads of state and government at the 2005 UN World Summit; (ii) early lessons learned (2005-2010) in facing the growing conceptual, institutional, and political challenges that the practical implementation of the project would pose (see the UN Secretary’s report on Implementing R2P); (iii) maturity (2011-) with crystallizes in the explicit invocation of the principle in the Libya crisis (which Evans define as a “textbook case”) but also in the renewed concerns and caution out of the implementation of Resolution 1973 in Libya (whether NATO has gone beyond the UN mandate to protect the Libyan people) that help to explain the current paralysis over Syria. According to Professor Evans, the present situation calls for the “need to regain consensus” on the implementation on the principle. In this perspective he situates the current debate on the related concept of “Responsibility While Protecting” (RwP) as recently brought by Brazil’s Permanent Mission to the UN.

On a different note, Phoebe Wynn-Pope referred to the role of non-state actors and civil society in working with national, regional and international actors to respond to the threat of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. In this line, the Australia Red Cross handbook that she presented at the event states that “While these non-state actors are unlikely to have a ‘legal’ responsibility under international law, there is strong argument that a ‘moral’ responsibility exists”. In a similar vein, and expressing its disappointment with the exclusion of the civil society role on the RwP debate, the ICRtoP highlights that:

Civil society is crucial in monitoring the implementation of RtoP by actors at the national, regional, and international levels. NGOs also work to galvanize the political will to prevent and halt the four crimes through improving understanding of RtoP and alerting actors to at-risk situations.

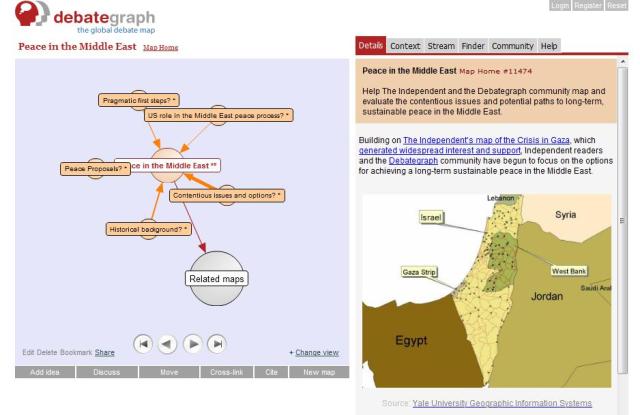

There are many examples in the emergent domain of crisis mapping showing how individuals, networks, and civil society organizations are already playing a significant role (see my previous post). But the uneasiness to accommodate the role of the civil society and other non-state actors within the paradigm of R2P goes far beyond of the debate on how this role can be effectively coordinated with the mandate of the States. Moral and legal responsibilities operate at different levels, and the former tend to creak under the structures of Westphalian states, their interests, and their international relations. R2P may certainly have infused a new language to the institutionalized indifference of Westphalian states. Yet, and despite having stroke a rare chord, the harmony remains Westphalian. It seems to me that perhaps it would be better to distinguish between the “narrow but deep” R2P principle that applies to the individual and collective action of the states under international law, and the ethics of responsibility that all citizens and civil society groups bear as they engage in preventing, denouncing, or documenting human rights violations. Please note that I’m referring here to an ethics of responsibility in the Emmanuel Levinas sense of responsibility for the Other: “I am responsible for the Other without waiting for reciprocity, were I to die for it. Reciprocity is his affair. It is precisely insofar as the relation between the Other and me is not reciprocal that I am subjection to the Other; and I am ’subject’ essentially in this sense” (E. Levinas. 1982 Ethics and Infinity – Conversations with Philippe Nemo. Pittsburgh (Pa): Duquesne University Press (1985 English Edition).

Emmanuel Levinas

In this perspective, it is difficult to imagine how states could be understood as “subjects” in the Levinasian sense. Even if this is a radical assumption, I think it remains useful to clarify the different dimensions of responsibilities and duties that states, organizations, and individuals bear.

Marta Poblet